guest post by John Christy, UAHuntsville, Alabama State Climatologist

Let me say two things up front. 1. The first 10 weeks of the summer of 2012 were brutally hot in some parts of the US. For these areas it was hotter than seen in many decades. 2. Extra greenhouse gases should warm the climate. We really don’t know how much, but the magnitude is more than zero, and likely well below the average climate model estimate.

Now to the issue at hand. The recent claims that July 2012 and Jan-Jul 2012 were the hottest ever in the conterminous US (USA48) are based on one specific way to look at the US temperature data. NOAA, who made the announcement, utilized the mean temperature or TMean (i.e. (TMax + TMin)/2) taken from station records after adjustments for a variety of discontinuities were applied. In other words, the average of the daily high and daily low temperatures is the metric of choice for these kinds of announcements.

Unfortunately, TMean is akin to averaging apples and oranges to come up with a rather uninformative fruit. TMax represents the temperature of a well-mixed lower tropospheric layer, especially in summer. TMin, on the other hand, is mostly a measurement in a shallow layer that is easily subjected to deceptive warming as humans develop the surface around the stations.

The problem here is that TMin can warm over time due to an increase in turbulent mixing (related to increasing local human development) which creates a vertical redistribution of atmospheric heat. This warming is not primarily due to the accumulation of heat which is the signature of the enhanced greenhouse effect. Since TMax represents a deeper layer of the troposphere, it serves as a better proxy (not perfect, but better) for measuring the accumulation of tropospheric heat, and thus the greenhouse effect. This is demonstrated theoretically and observationally in McNider et al. 2012. I think TMax is a much better way to depict the long-term temperature character of the climate.

With that as a introduction, the chart of TMax generated by Roy in this post, using the same USHCNv2 stations as NOAA, indicates July 2012 was very hot, coming in at third place behind the scorching summers of 1936 and 1934. This is an indication that the deeper atmosphere, where the greenhouse effect is more directly detected, was probably warmer in those two years than in 2012 over the US.

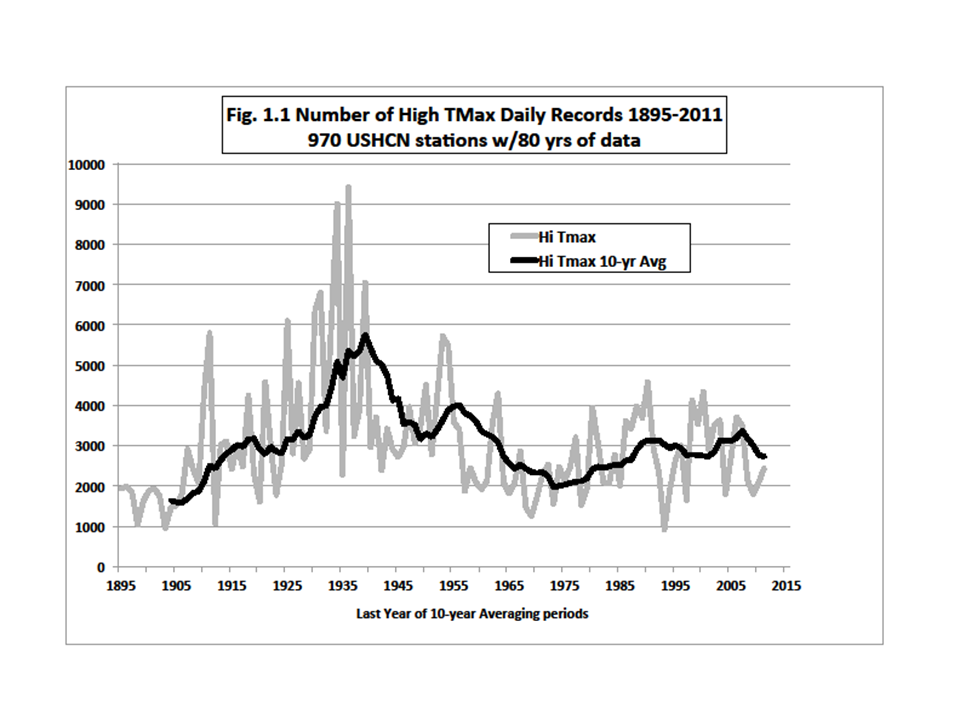

Another way to look at the now diminishing heat wave is to analyze stations with long records for the occurrence of daily extremes. For USA48 there are 970 USHCN stations with records at least 80 years long. In Fig. 1.1 is the number of record hot days set in each year by these 970 stations (gray). The 1930s dominate the establishment of daily TMax record highs (click for full-size):

But for climatologists, the more interesting result is the average of the total number of records in ten-year periods to see the longer-term character. The smooth curve shows that 10-year periods in the 1930s generated about twice as many hot-day records as the most recent decades. Note too, that if you want to find a recent, unrepresentative, “quiet” period for extremes, the 1950s to 1970s will do (see Part 2 to be posted later).

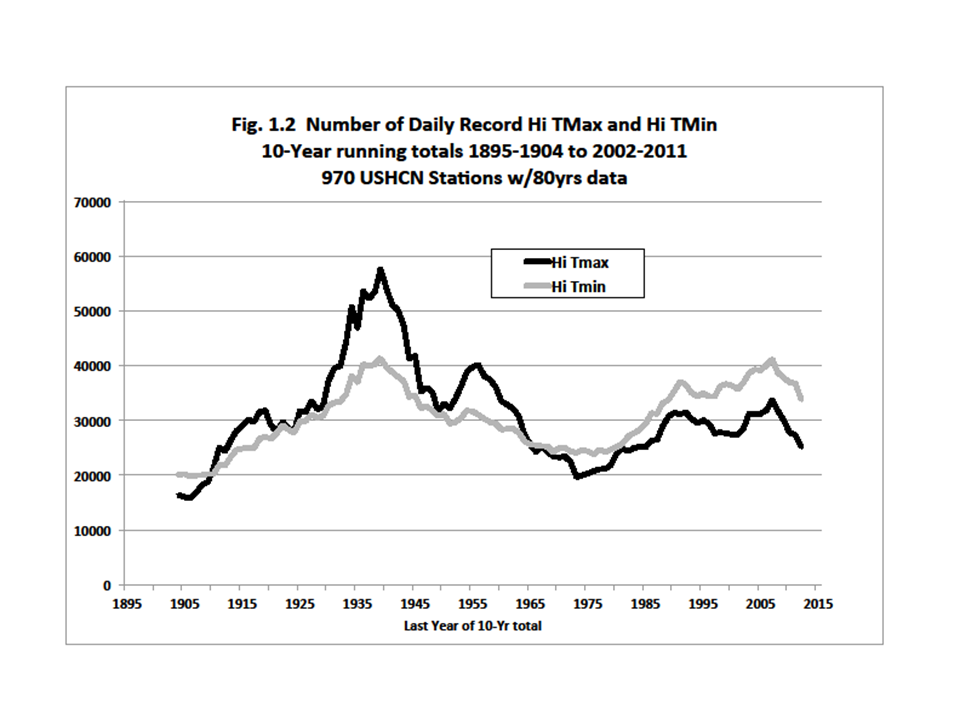

Figure 1.2 below compares the ten-year averages between high TMax and high TMin records:

There has been a relatively steady rise in high TMin records (i.e. hot nights) which does not concur with TMax, and is further evidence that TMax and TMin are not measuring the same thing. They really are apples and oranges. As indicated above, TMin is a poor proxy for atmospheric heat content, and it inflicts this problem on the popular TMean temperature record which is then a poor proxy for greenhouse warming too.

Before I leave this plot, someone may ask, “But what about those thousands of daily records that we were told were broken this year?” Unfortunately, there is a lot of confusion about that. Records are announced by NOAA for stations with as little as 30 years of data, i.e. starting as late as 1981. As a result, any moderately hot day now will generate a lot of “record highs.” But, most of those records were produced by stations which were not operating during the heat waves of the teens, twenties, thirties and fifties. That is why the plots I’ve provided here tell a more complete climate story. As you can imagine, the results aren’t nearly so dramatic and no reporter wants to write a story that says the current heat wave was exceeded in the past by a lot. Readers and viewers would rather be told they are enduring a special time in history I think.

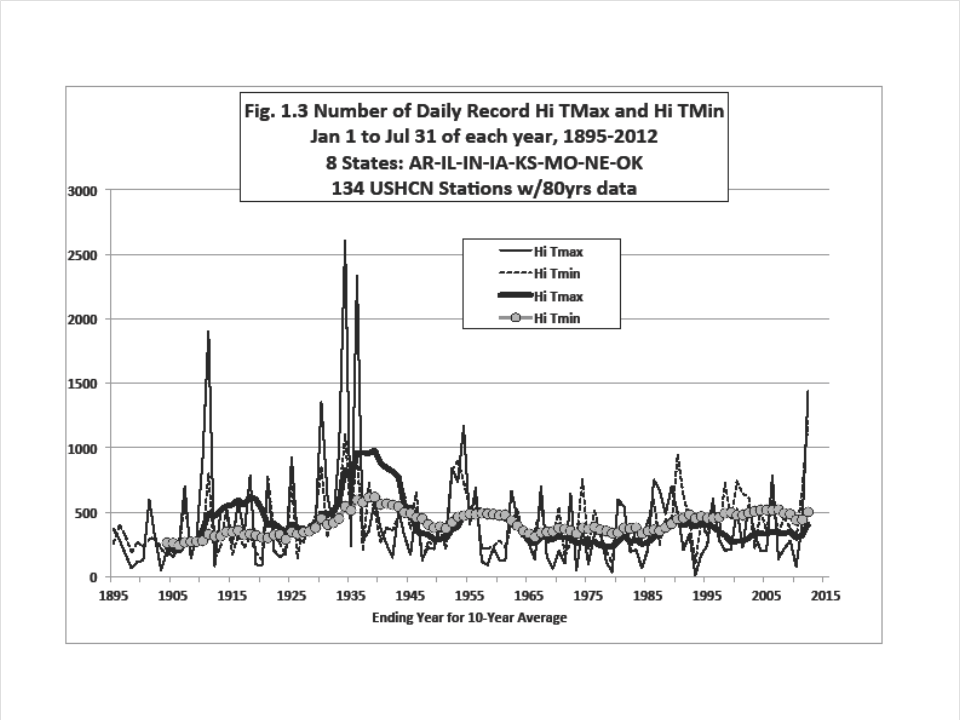

Because the central US was the focus of the recent heat, I generated the number of Jan-Jul record high daily TMaxs for eight states, AR, IL, IN, IA, KS, MO, NE and OK that includes 2012 (Fig. 1.3):

(Because a few stations were late, I multiplied the number in 2012 by 1.15 to assure their representation). For these states, there is no doubt that the first seven months of 2012 haven’t seen as many record hot days since the 1930s. In other words, for the vast majority of residents of the Central US, there were more days this year that were the “hottest ever” over their lifetimes. (Notice too, that the ten-year averages of TMax and TMin records mimic the national results – high TMin records are becoming more frequent while TMax records have been flat since the 1930s.)

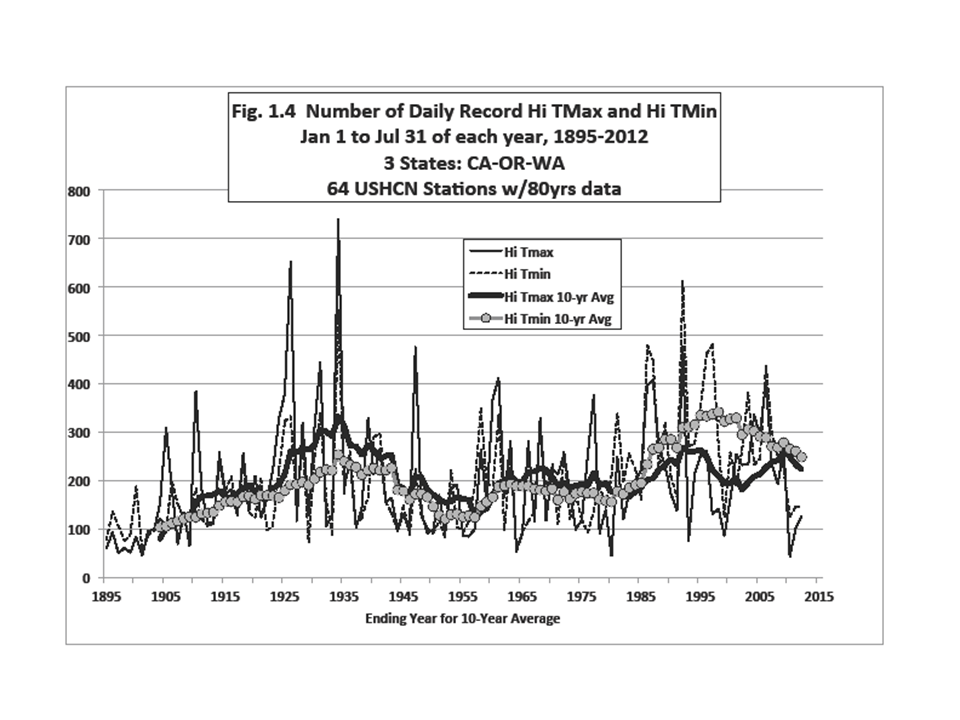

The same plot for the west coast states of CA, OR and WA (Fig. 1.4) shows that the last three years (Jan-Jul only) have seen a dearth of high temperature records:

However, even with these two very different climates, one feature is consistent – the continuously rising number of record hot nights relative to record hot days. This increase in hot nights is found everywhere we’ve looked. Unfortunately because many scientists and agencies use TMean (i.e. influenced by TMin) as a proxy for greenhouse-gas induced climate change, their results will be misleading in my view.

I keep mentioning that the deep atmospheric temperature is a better proxy for detecting the greenhouse effect than surface temperature. Taking the temperature of such a huge mass of air is a more direct and robust measurement of heat content. Our UAHuntsville tropospheric data for the USA48 show July 2012 was very hot (+0.90°C above the 1981-2010 average), behind 2006 (+0.98 °C) and 2002 (+1.00 °C) and just ahead of 2011 (+0.89 °C). The differences (i.e. all can be represented by +0.95 ±0.06) really can’t be considered definitive because of inherent error in the dataset. So, in just the last 34 Julys, there are 3 others very close to 2012, and at least one or two likely warmer.

Then, as is often the case, the weather pattern that produces a sweltering central US also causes colder temperatures elsewhere. In Alaska, for example, the last 12 months (-0.82 °C) have been near the coldest departures for any 12-month period of the 34 years of satellite data.

In the satellite data, the NH Land anomaly for July 2012 was +0.59 °C. Other hot Julys were 2010 +0.69, and 1998 at +0.67 °C. Globally (land and ocean), July 2012 was warm at +0.28 °C, being 5th warmest of the past 34 Julys. The warmest was July 1998 at +0.44 °C. (In Part 2, I’ll look at recent claims about Northern Hemisphere temperatures.)

So, what are we to make of all the claims about record US TMean temperatures? First, they do not represent the deep atmosphere where the enhanced greenhouse effect should be detected, so making claims about causes is unwise. Secondly, the number of hot-day extremes we’ve seen in the conterminous US has been exceeded in the past by quite a bit. Thirdly, the first 10 weeks of 2012’s summer was the hottest such period in many parts of the central US for residents born after the 1930’s. So, they are completely justified when they moan, “This is the hottest year I’ve ever seen.”

By the way, for any particular period, the hottest record has to occur sometime.

REFERENCE

McNider, R.T., G.J. Steeneveld, A.A.M. Holtslag, R.A. Pielke Sr., S. Mackaro, A. Pour-Biazar, J. Walters, U. Nair, and J.R. Christy, 2012: Response and sensitivity of the nocturnal boundary layer over land to added longwave radiative forcing. J. Geophys. Res., 117, D14106, doi:10.1029/2012JD017578.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog

We can feel more that the temperature is higher than before.

This increase in hot nights is found everywhere weve looked.

In a guest post by John Christy, UAHuntsville, Alabama State Climatologist, the author argues that the recent claims that July 2012 and Jan-Jul 2012 were the hottest ever in the contiguous US are based on an average of the daily high and low temperatures (TMean), which is a flawed metric. The author claims that TMin is a poor proxy for atmospheric heat content and is easily subjected to deceptive warming due to increased local human development. The author suggests that TMax, which represents a deeper layer of the troposphere and is a better proxy for measuring the greenhouse effect, is a better way to depict the long-term temperature character of the climate. The author presents data showing that the number of record hot days set in the 1930s was twice as many as in the most recent decades, and there has been a steady rise in high TMin records, which is evidence that TMax and TMin are not measuring the same thing. https://www.flex.storage/