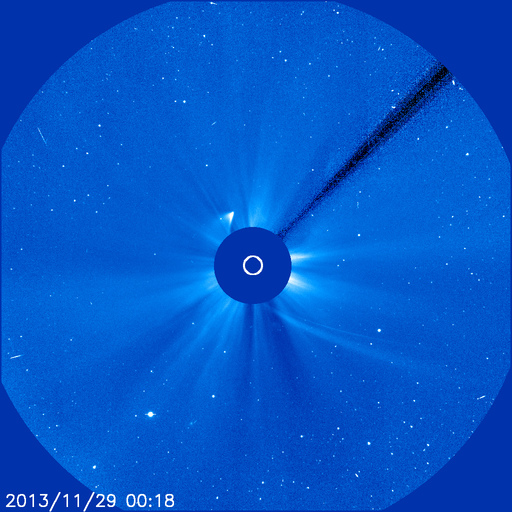

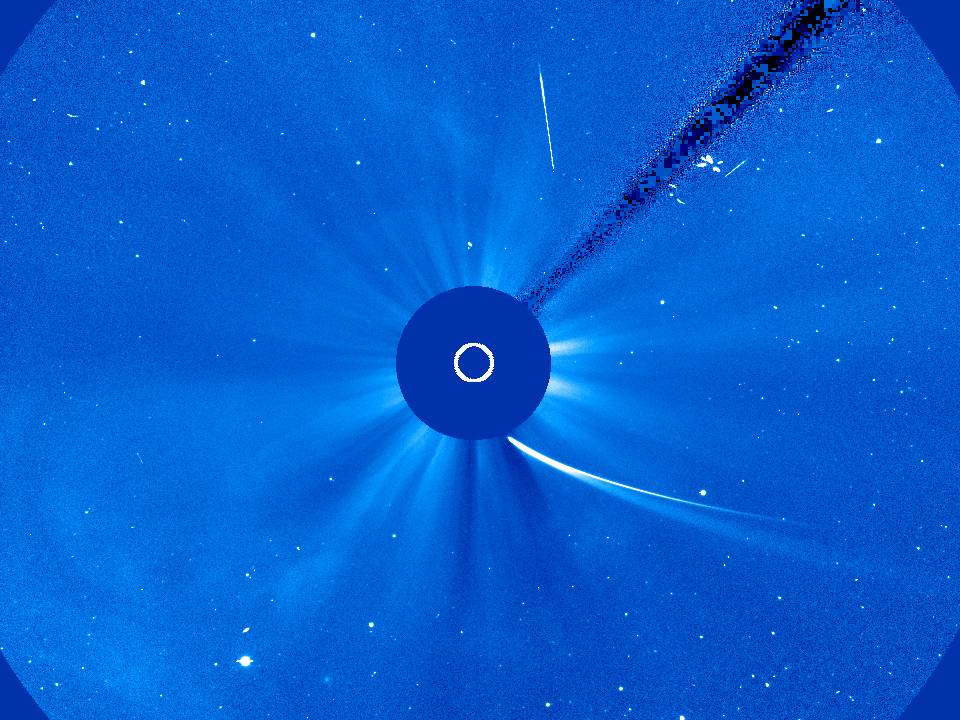

As I surmised yesterday, it appears that the nucleus of Comet ISON was mostly destroyed during its close approach to the sun, and what remains is fading fast, now estimated to be magnitude 5 in brightness:

According to Karl Battams’ recent blog post,

“…during its passage through the Sun’s million-degree corona, its dusty/gassy coma got very much burned away, though clearly some fine dust survived (which is the fine cloudy stuff you see being pushed away from the Sun).”

(His post also has a couple of very cool animations from the STEREO spacecraft, so I encourage you to take a look.)

Why does the comet appear the way it does now, after perihelion? Here’s a semi-technical explanation…what I’ve surmised based upon my knowledge from atmospheric science.

Basically, the material being flung out sideways from the comet’s normal orbital path is very fine, whereas the particles in the “head” are larger. Although the reasons for this are not discussed in other blogs posts about the comet, I suspect it is the same reason why tiny particles of rock can float in the air as aerosols, whereas large particles would fall to the Earth. Or, why fine sediment particles are suspended in a river, while large particles fall to the bottom.

Gravitational forces act on the mass of an object, whereas atmospheric or liquid viscous pressure forces act on the physical size (cross-sectional area) of the object. Because mass increases as the 3rd power of the particle radius, and physical size (or cross-sectional area) increases as only the 2nd power, the larger a particle is, the greater the gravitational effects are relative to pressure forces.

In the case of the comet, the pressure forces are from radiation pressure and the solar wind. As the nucleus of Comet ISON got pulverized during perihelion, the tiniest particles were more affected by the radiation pressure and solar wind than by gravity, and they got “blown away” from the normal orbital path. As I mentioned in my last post, they appear to be “flung outward”, away from the normal gravitationally-dominated orbital path of the comet nucleus.

If you watch the above video, you will see this fine material being blown in the solar wind, away from the nucleus. Presumably, what is left in the nucleus are somewhat larger particles whose path is still dominated by gravity, but there is so little left that there is not much there to reflect sunlight that we can see.

I suspect that in the coming days only the better telescopes will be able to see what is left of the comet. Astrophotographers like me will see very little if anything at all.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog