Global warming “problem” cut by 50%

As readers here are aware, I don’t usually critique published climate papers unless they are especially important to the climate debate. Too many papers are either not that important, or not that convincing to me.

The holy grail of the climate debate is equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS): just how much warming (and thus associated climate change) will occur in response to an eventual doubling of the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere?

Yesterday’s early online release of a new paper by Nicholas Lewis and Judith Curry (“The impact of recent forcing and ocean heat uptake data on estimates of climate sensitivity“, Journal of Climate) represents one of those seminal papers.

It is an extension of a previously published paper by Lewis & Curry, adding more data, and addressing criticisms of their earlier work. Its methodology isn’t entirely original, since previous (but somewhat preliminary) work along the same lines (Otto et al., 2013) has resulted in observational estimates of relatively low climate sensitivity compared to the IPCC climate models.

But what is notable to me is (1) the comprehensive extent to which methodological and data uncertainties have been addressed, and (2) the fact it was published in the relatively mainstream and consensus-defending Journal of Climate.

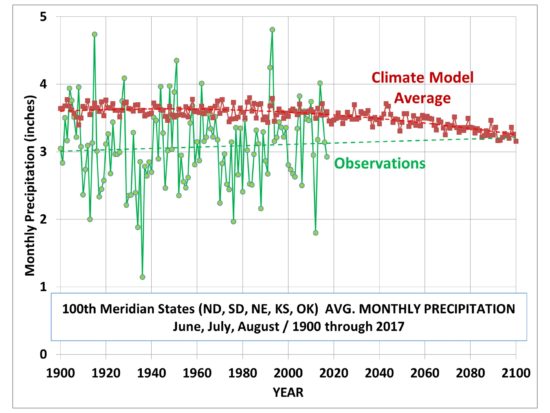

Basically, the paper concludes that the amount of surface and deep-ocean warming that has occurred since the mid- to late-1800s is consistent with low equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) to an assumed doubling of atmospheric CO2. They get a median estimate of 1.66 deg. C (1.50 deg. C without uncertain infilled Arctic data), which is only about half of the average of the IPCC climate models. It is just within the oft-quoted range of 1.5 to 4.5 deg. C that the IPCC has high confidence ECS should occupy.

The last I knew, Lewis’s belief is that the biggest uncertainty in the ECS calculation is how accurate the assumed forcings are that must be used to make the ECS computation (over the last ~130 years, the climate system has stored a certain amount of extra energy in the ocean, and shed a certain amount of energy to space from increased surface temperatures, in response to assumed changes in radiative forcing…. a big uncertainty in which is assumed anthropogenic aerosol-related cooling).

I’d like to additionally emphasize overlooked (and possibly unquantifiable) uncertainties: (1) the assumption in studies like this that the climate system was in energy balance in the late 1800s in terms of deep ocean temperatures; and (2) that we know the change in radiative forcing that has occurred since the late 1800s, which would mean we would have to know the extent to which the system was in energy balance back then.

We have no good reason to assume the climate system is ever in energy balance, although it is constantly readjusting to seek that balance. For example, the historical temperature (and proxy) record suggests the climate system was still emerging from the Little Ice Age in the late 1800s. The oceans are a nonlinear dynamical system, capable of their own unforced chaotic changes on century to millennial time scales, that can in turn alter atmospheric circulation patterns, thus clouds, thus the global energy balance. For some reason, modelers sweep this possibility under the rug (partly because they don’t know how to model unknowns).

But just because we don’t know the extent to which this has occurred in the past doesn’t mean we can go ahead and assume it never occurs.

Or at least if modelers assume it doesn’t occur, they should state that up front.

If indeed some of the warming since the late 1800s was natural, the ECS would be even lower.

Now the question is: At what point will the IPCC (or, maybe I should say climate modelers) start recognizing that their models are probably too sensitive? Remember, the sensitivity of their models is NOT the result of basic physics, as some folks claim… it’s the result of very uncertain parameterizations (e.g. clouds) and assumptions (e.g. precipitation efficiency effects on the atmospheric water vapor profile and thus feedback). The models are adjusted to produce warming estimates that “look about right” to the modelers. Yes, *some* amount of warming from increasing CO2 is reasonable from basic physics. But just how much warming is open to manipulation within the uncertain portions of the models.

Maybe it’s time for the modelers to change their opinion of how much warming “looks about right”.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog