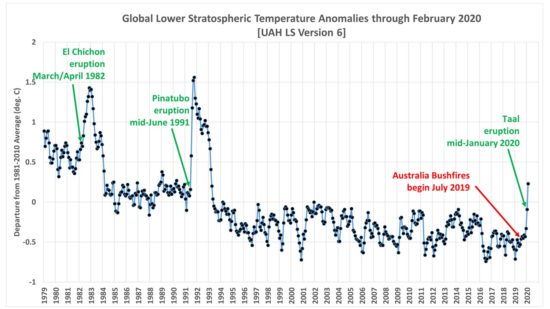

Today (Monday, March 30) is the 30th anniversary of our publication in Science describing the first satellite-based dataset for climate monitoring.

While much has happened in the last 30 years, I thought it might be interesting for people to know what led up to the dataset’s development, and some of the politics and behind-the-scenes happenings in the early days. What follows is in approximate chronological order, and is admittedly from my own perspective. John Christy might have somewhat different recollections of these events.

Some of what follows might surprise you, some of it is humorous, and I also wanted to give credit to some of the other players. Without their help, influence, and foresight, the satellite temperature dataset might never have been developed.

Spencer & Christy Backgrounds

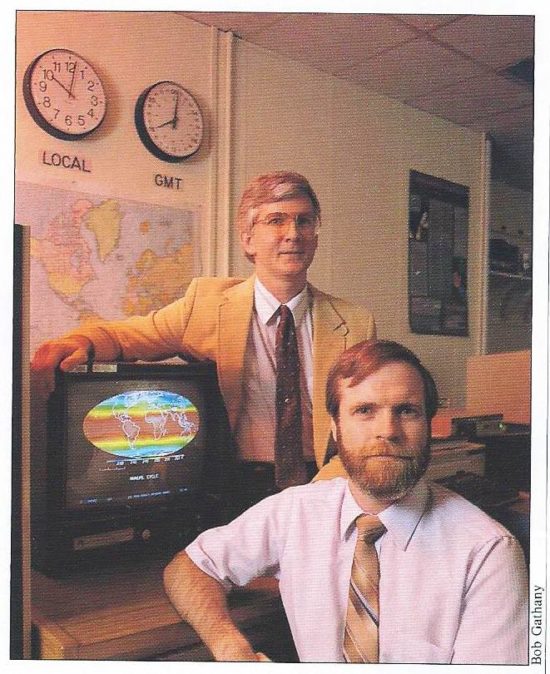

In the late 1980s John Christy and I were contractors at NASA/MSFC in Huntsville, AL, working in the Atmospheric Sciences Division where NASA managers and researchers were trying to expand beyond their original mission, which was weather support for Space Shuttle launches. NASA/MSFC manager Gregory S. Wilson was a central figure in our hiring and encouragement of our work.

I came from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a Ph.D. in Meteorology, specializing in the energetics of African easterly waves (the precursors of most Atlantic hurricanes). I then did post-doc work there in the satellite remote sensing of precipitation using microwave radiometers. John Christy received his Ph.D. in Atmospheric Science from the University of Illinois where he did his research on the global surface atmospheric pressure field. John had experience in analyzing global datasets for climate research, and was hired to assist Pete Robertson (NASA) to assist in data analysis. I was hired to develop new microwave satellite remote sensing projects for the Space Shuttle and the Space Station.

James Hansen’s Congressional Testimony, and Our First Data Processing

In 1988, NASA’s James Hansen testified for then-Senator Al Gore, Jr., testimony which more than any single event thrust global warming into the collective consciousness of society. We were at a NASA meeting in New Hampshire. As I recall, UAH’s Dick McNider on the plane ride up had just read a draft of a paper by Kevin Trenberth given to him by John Christy (who had been a Trenberth student) that discussed many issues with the sparse surface temperature data for detecting climate change.

During lunch Dick asked, given all the issues with the lack of global coverage and siting issues with surface data sets discussed by Trenberth, if there wasn’t satellite data that could be used to investigate Hansen’s global claims? NASA HQ manager James Dodge was there and expressed immediate interest in funding such a research project.

I said, yes, such data existed from the NOAA/NASA/JPL Microwave Sounding Unit (MSU) instruments, but it would be difficult to access approximately 10 years of global data. Note that this was before there was routine internet access to large digital datasets, and ordering data from the government had a very large price tag. No one purchased many years of global data; it came on computer 6250 bpi computer tapes each containing approximately 100 MB of data, and computers then were pretty slow. The data we wanted was from NOAA satellites, and NOAA would reuse these large (10.5 inch) IBM tapes rather than to keep the old data tapes around using up storage space.

It turns out that Roy Jenne who worked data systems at the NSF’s National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder had years before taken it upon himself to archive the old NOAA satellite data before it was lost altogether. He kept the data on a “mass storage system” (very large and inefficient by today’s standards) and I believe it was Greg Wilson who John Christy made the connection to gain us access to those data.

We obtained somewhat less than 10 years of data from NCAR, and I decided how to best calibrate it and average it into a more manageable space/time resolution. I had frequent contact with JPL engineers who built the MSU instruments, Fred Soltis in particular, who along with Norman Grody at NOAA provided me with calibration data for the MSU instruments flying on different satellites.

We enlisted John Christy to analyze those data since he brought considerable experience with diagnosing global datasets for climate purposes. One of the first things John discovered was from comparing global averages from different satellites in different orbits: They gave surprisingly similar answers in terms of year-to-year temperature variability. This was quite unexpected and demonstrated that the MSU instruments had high calibration stability, at least over a few years. It also demonstrated that NOAA’s practice of adjusting satellite data with radiosondes (weather balloons) was backwards: the differences others had seen between the two systems were due to poor spatial sampling by the radiosondes, not due to changes in the satellite calibration stability.

In addition to the critical historical data archived by Roy Jenne at NCAR, we would some of the more recent satellite data that was kept at NOAA. We didn’t have quite ten years of data, and an editor at Science magazine wanted ten full years of data before they would publish our first findings. We were able to order more data from NOAA to get the first 10 years’ worth (1979 through 1988), and Science accepted our paper.

The NASA Press Conference

On March 29, 1990 we held a “media availability” at the communications center at NASA/MSFC. For some reason, NASA would not allow it to be called a full-fledged “press conference”. As I recall, attendance was heavy (by Huntsville standards) and there was no place for me to park but in the grass, for which I was awarded a parking ticket by NASA security. JPL flew a remaining copy of the MSU instrument in as a prop; it had its own seat on a commercial flight from Pasadena.

Jay Leno would later mention our news conference in his monologue, and Joan Lunden covered it on Good Morning America. While we watched Ms. Lunden on a monitor the next morning, a NASA scientist remarked that he was too distracted by her long, slender legs to listen to what she was saying.

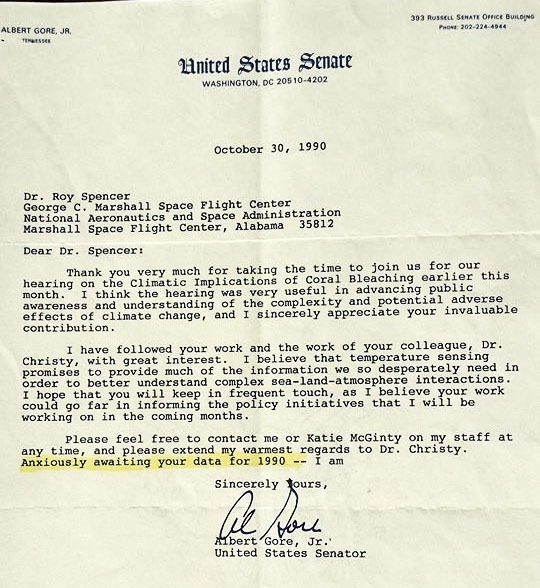

Our 1990 Senate Testimony for Gore

After we published our first research results on March 30,1990, we received an invitation to testify for Al Gore in a Senate committee hearing in October, 1990 on the subject of coral bleaching. Phil Jones from the University of East Anglia was also there to testify.

As people filed into the hearing room, I saw a C-SPAN camera being set up, and having noticed that Al Gore seemed to be the only committee member in attendance, I asked the cameraman about the lack of interest from other senators. He said something like, “Oh, Senator Gore likes it this way… he gets all the media attention.”

We still used overhead projectors back then with view graphs, and I thought I’d better check out the equipment. The projector turned out to be seriously out-of-focus, and the focus adjustment on the arm would not fix it. I remember thinking to myself, “this seems pretty shoddy for Congress”.

Senator Gore launched into some introductory remarks while looking at me as I struggled with the projector. From his comments, he was obviously assuming I was Phil Jones (who was supposed to go first, and who Gore said he had previously visited in England). I thought to myself, this is getting strange. Just in time, I realized the projector arm was bent slightly out of alignment, I bent it back, and took my seat while Phil Jones presented his material.

Our testimony, which was rather uneventful, led to the traditional letter of thanks from Gore for supporting the hearing. In that letter, Gore expressed interest in additional results as they became available.

So, when it came time to get the necessary additional satellite data out of NOAA, I dropped Gore’s name to a manager at NOAA who suddenly became interested in providing everything they had to us at no charge… rather than us having to pay tens of thousands of our research dollars.

Hundreds of Computer Tapes and an Old Honda Civic

It might seem absurd to today’s young scientists, but it was not an easy task to process large amounts of digital data in the late 1980s. I received box after box of 9-track computer tapes in the mail from NOAA. Every few days, I would load them up in my old, high-mileage, barely-running 2-door Honda Civic and cart them over to the computer center at MSFC.

NASA’s Greg Wilson had gotten permission to use the computer facility for the task. At that time, most of the computer power was being taken up by engineers modeling the fuel flows within the Space Shuttle main engines. As I added more data and processed it, I would pass the averages on to John Christy who would then work his analysis magic on them.

I don’t recall how many years we would use this tape-in-the-mail ordering system. Most if not all of those tapes now reside in a Huntsville landfill. After many years of storage and hauling them from one office location to another during our moves, I decided there was no point in keeping them any longer.

A Call from the White House, and the First Hubble Space Telescope Image

Also in 1990, John Sununu, White House Chief of Staff to President George H. W. Bush, had taken notice of our work and invited us to come up to DC for a briefing.

We first had to bring the NASA Administrator V. Adm. Richard Truly up to speed. Truly was quite interested and was trying to make sure he understood my points by repeating them back to me. In my nervousness, I was apparently interrupting him by finishing his sentences, and he finally told me to “shut up”. So, I shut up.

The next stop was the office of the Associate Administrator, Lennard Fisk. While we were briefing Fisk, an assistant came in to show him the first image just collected by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). This was before anyone realized the HST was miss-assembled and was out of focus. In retrospect, it was quite a fortuitous coincidence that we were there to witness such an event.

As the day progressed, and no call was coming in from the White House, Dr. Fisk seemed increasingly nervous. I was getting the impression he really did not want us to be briefing the White House on something as important as climate change. In those days, before NASA’s James Hansen made it a habit, no scientists were allowed to talk to politicians without heavy grooming by NASA management.

As the years went by, we would learn that the lack of substantial warming in the satellite data was probably hurting NASA’s selling of ‘Mission to Planet Earth’ to Congress. The bigger the perceived problem, the more money a government agency can extract from Congress to research the problem. At one point a NASA HQ manager would end up yelling at us in frustration for hurting the effort.

Late in the afternoon the call finally came in from the White House for us to visit, at which point Dr. Fisk told them, “Sorry, but they just left to return to Huntsville”, as he ushered us out the door. Dr. Wilson swore me to secrecy regarding the matter. (I talked with John Sununu at a Heartland Institute meeting a few years ago but forgot to ask him if he remembered this course of events). This would probably be – to me, at least – the most surreal and memorable day of our 30+ years of experiences related to the satellite temperature dataset.

After 1990

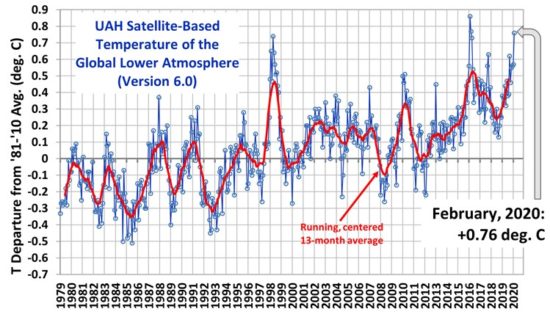

In subsequent years, John Christy would assume the central role in promoting the satellite dataset, including extensive comparisons of our data to radiosonde data, while I spent most of my time on other NASA projects I was involved in. But once a month for the next 30 years, we would process the most recent satellite data with our separate computer codes, passing the results back and forth and posting them for public access.

Only with our most recent Version 6 dataset procedures would those codes be entirely re-written by a single person (Danny Braswell) who had professional software development experience. In 2001, after tiring of being told by NASA management what I could and could not say in congressional testimony, I resigned NASA and continued my NASA projects as a UAH employee in the Earth System Science Center, for which John Christy serves as director (as well as the Alabama State Climatologist).

At this point, neither John nor I have retirement plans, and will continue to update the UAH dataset every month for the foreseeable future.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog