Summary

The Energy Information Agency (EIA) projects a growth in energy-based CO2 emissions of +0.6%/yr through 2050. But translating future emissions into atmospheric CO2 concentration requires a global carbon budget model, and we frequently accept the United Nations reliance on such models to tell us how much CO2 will be in the atmosphere for any given CO2 emissions scenario. Using a simple time-dependent CO2 budget model forced with yearly estimates of anthropogenic CO2 emissions and optimized to match Mauna Loa observations, I show that the EIA emissions projections translate into surprisingly low CO2 concentrations by 2050. In fact, assuming constant CO2 emissions after 2050, the atmospheric CO2 content eventually stabilizes at just under 2XCO2.

Introduction

I have always assumed that we are on track for a doubling of atmospheric CO2 (“2XCO2”), if not 3XCO2 or 4XCO2. After all, humanity’s CO2 emissions continue to increase, and even if they stop increasing, won’t atmospheric CO2 continue to rise?

It turns out, the answer is probably “no”.

The rate at which nature removes CO2 from the atmosphere, and what controls that rate, makes all the difference.

Even if we knew exactly what humanity’s future CO2 emissions were going to be, how much Mother Nature takes out of the atmosphere is seldom discussed or questioned. This is the domain of global carbon cycle models which we seldom hear about. We hear about the improbability of the RCP8.5 concentration scenario (which has gone from “business-as-usual”, to “worst case”, to “impossible”), but not much about how those CO2 concentrations were arrived at from CO2 emissions data.

So, I wanted to address the question, What is the best estimate of atmospheric CO2 concentrations through the end of this century, based upon the latest estimates of future CO2 emissions, and taking into account how much nature has been removing from the atmosphere?

As we produce more and more CO2, the amount of CO2 removed by various biological and geophysical processes also goes up. The history of best estimates of yearly anthropogenic CO2 emissions, combined with the observed rise of atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa, Hawaii, tells us a lot about how fast nature adjusts to more CO2.

As we shall see, it is entirely possible that even if we continued producing large quantities of CO2, those levels in the atmosphere might eventually stabilize.

In their most recent 2019 report, the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) projects that energy-based emissions of CO2 will grow at 0.6% per year until 2050, which is what I will use to project future atmospheric CO2 concentrations. I will show what this emissions scenario translates into using a simple atmospheric CO2 budget model that has been calibrated with the Mauna Loa CO2 observations. And we will see that the resulting remaining amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is surprisingly low.

A Review of the CO2 Budget Model

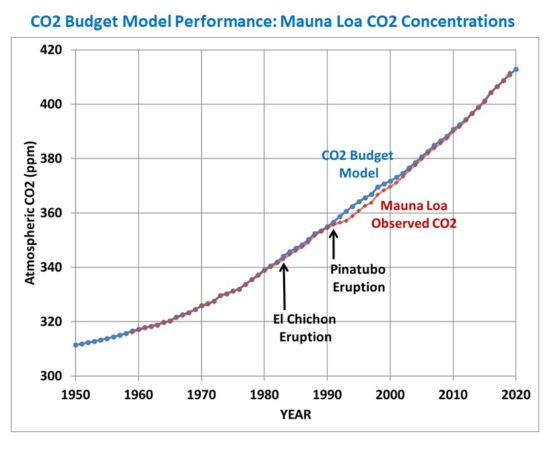

I previously presented a simple time-dependent CO2 budget model of global atmospheric CO2 concentration that uses (1) yearly anthropogenic CO2 emissions, along with (2) the central assumption (supported by the Mauna Loa CO2 data) that nature removes CO2 from the atmosphere at a rate in direct proportion to how high atmospheric CO2 is above some natural level the system is trying to ‘relax’ to.

As described in my previous blog post, I also included an empirical El Nino/La Nina term since El Nino is associated with higher CO2 in the atmosphere, and La Nina produces lower concentrations. This captures the small year-to-year fluctuations in CO2 from ENSO activity, but has no impact on the long-term behavior of the model.

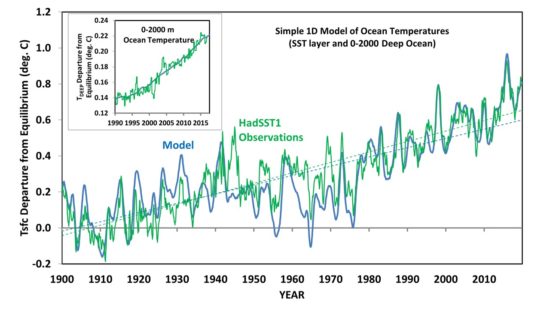

The model is initialized in 1750 with the Boden et al. (2017) estimates of year anthropogenic emissions, and produces an excellent fit to the Mauna Loa CO2 observations using the assumption of a baseline (background) CO2 level of 295 ppm and a natural removal rate of 2.33% per year of the atmospheric excess above that baseline.

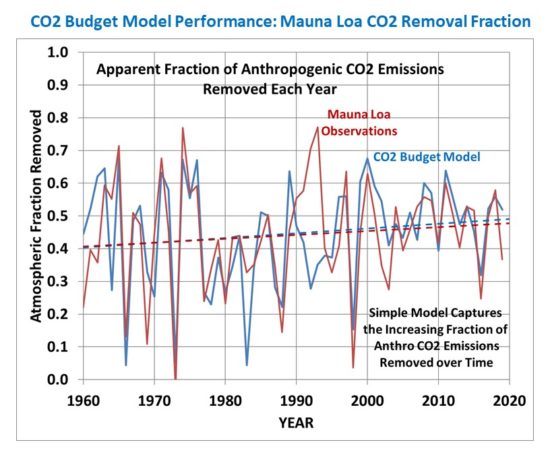

Here is the resulting fit of the model to Mauna Loa data, with generally excellent results. (The post-Pinatubo reduction in atmospheric CO2 is believed to be due to increased photosynthesis due to an increase in diffuse sunlight penetration into forest canopies caused by the volcanic aerosols):

The model even captures the slowly increasing trend in the apparent yearly fractional removal of CO2 emissions.

Model Projections of Atmospheric CO2

I forced the CO2 model with the following two future scenario assumptions:

1) EIA assumption of 0.6% per year growth in emissions through 2050

2) Constant emissions from 2050 onward

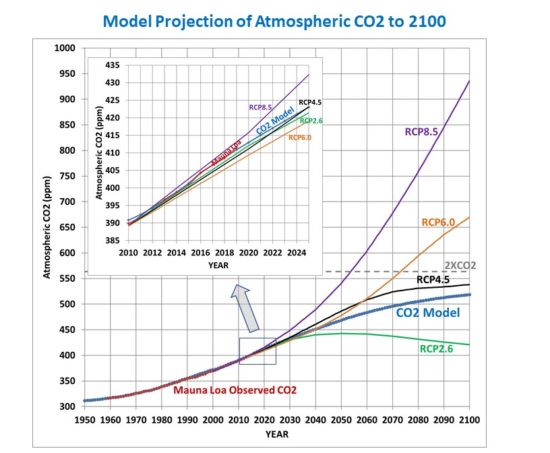

The resulting CO2 concentrations are shown in Fig. 3, along with the UN/IPCC CO2 concentration scenarios, RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0, and RCP8.5, used in the CMIP5 climate model projections.

Interestingly, with these rather reasonable assumptions regarding CO2 emissions, the model does not even reach a doubling of atmospheric CO2, and reaches an equilibrium CO2 concentration of 541 ppm in the mid-2200s.

Discussion

In my experience, the main complaint about the current model will be that it is “too simple” and therefore probably incorrect. But I would ask the reader to examine how well the simple model assumptions explain 60 years of CO2 observations (Figs. 1 & 2).

Also, I would recall the faulty predictions many years ago by the global carbon cycle modelers that the Earth system could not handle so much atmospheric CO2, and that the fraction which is removed over time would start to decrease. As Fig. 2 (above) shows, that has not happened. Maybe when it comes to photosynthesis, more life begets still more life, leading to a slowly increasing ability of the biosphere to remove excess CO2 from the atmosphere.

Given the large uncertainties in how the global carbon cycle responds to more CO2 in the atmosphere, it is entirely reasonable to hypothesize that the rate at which the ocean and land removes CO2 from the atmosphere is simply proportional to how high the atmospheric concentration gets above some baseline value. This simple hypothesis does not necessarily imply that the processes controlling CO2 sources and sinks are also simple; only that the net global rate of removal of atmospheric CO2 can be parameterized in a very simple form.

The Mauna Loa CO2 data clearly supports that hypothesis (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). And the result is that, given the latest projections of CO2 emissions, future CO2 concentrations will not only be well below the RCP8.5 scenario, but might not even be as high as RCP4.5, with atmospheric CO2 concentrations possibly not even reach a doubling (560 ppm) of estimated pre-Industrial levels (280 ppm) before leveling off. This result is even without future reductions in CO2 emissions, which is a possibility as new energy technologies become available.

I think this is at least as important an issue to discuss as the implausibility (impossibility?) of the RCP8.5 scenario. And it raises the question of just how good the carbon cycle models are that the UN IPCC depends upon to translate anthropogenic emissions to atmospheric CO2 observations.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog