Summers in the U.S. are hot. They always have been. Some are hotter than others.

Speaking as a PhD meteorologist with 40 years experience, this week’s heat wave is nothing special.

But judging from the memo released on June 22 by Public Citizen (a $17 million per year liberal/progressive consumer rights advocacy group originally formed by Ralph Nader in 1971 and heavily funded by Leftwing billionaire George Soros’s Open Society Foundations), every heat wave must now be viewed as a reminder of human-caused climate change. The memo opines that (believe it or not) the news media have not been very good about linking weather events to climate change, which is leading to complacency among the public.

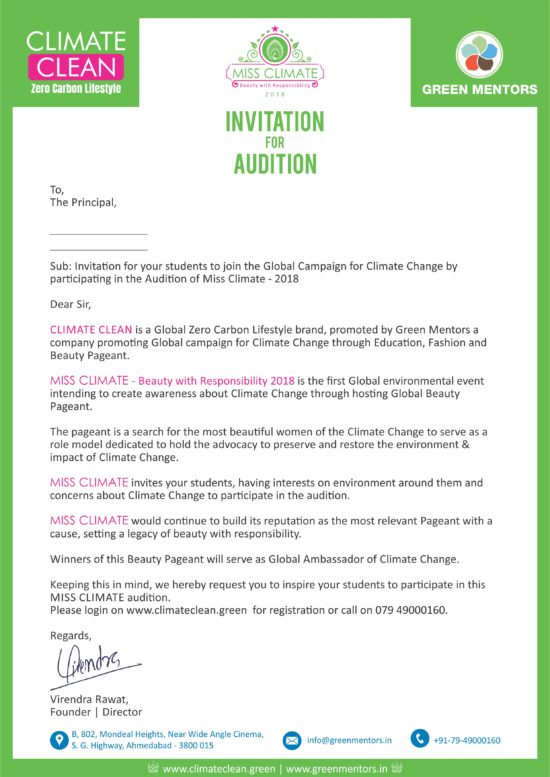

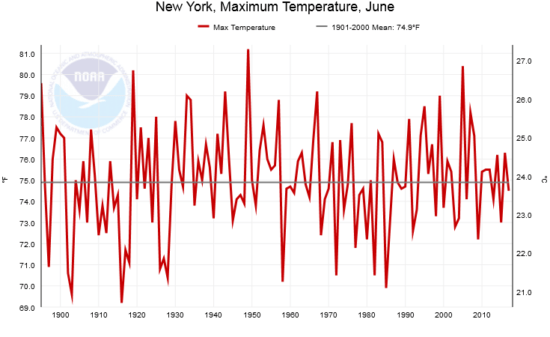

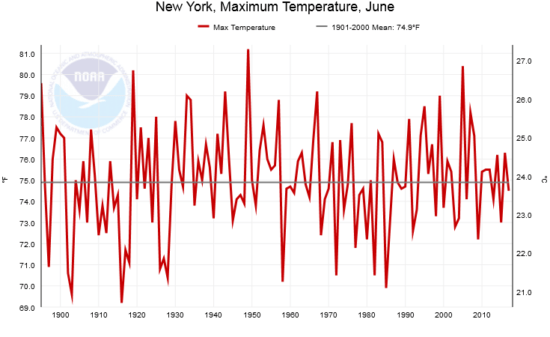

The June 22 memo focus was on the excessive heat in New York state, so let’s begin our journey down Hysteria Lane there. The official NOAA average maximum temperatures for every June since 1895 in New York looks like this:

Fig. 1. Average June maximum temperatures in New York state for every year from 1895 through 2017 (Source: NOAA)

The long term trend is not statistically different from zero. June 2018 is not yet available at the NOAA website, but from what I’ve seen for the global June Climate Forecast System map at WeatherBell.com, it looks like it was near the long-term (20th Century) average.

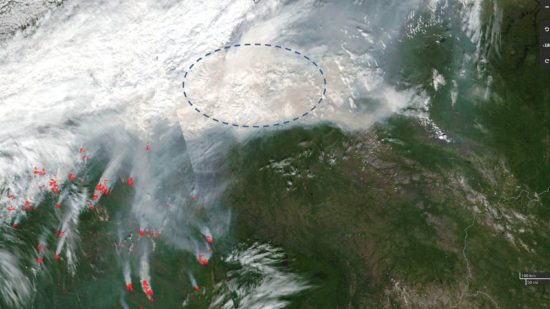

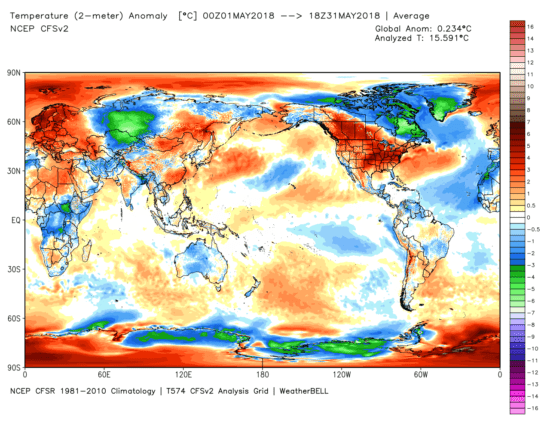

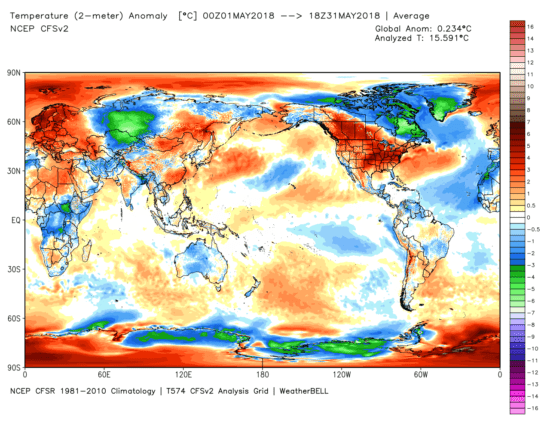

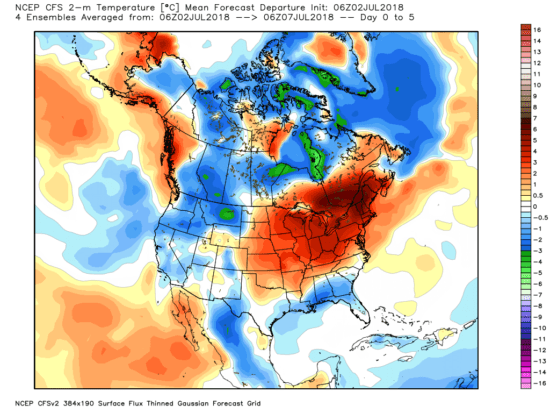

The memo also made mention of the widespread record warmth the U.S. experienced in May, 2018. New York had it’s 7th warmest May on record this year, and the long-term linear warming trend there since 1895 is weak (0.22 F/decade) and not statistically different from zero at the 95% confidence level. The May warmth in the U.S. was regional, as expected for weather variations, with much of Canada being exceedingly cold:

Fig. 2. NOAA CFS model-diagnosed surface temperature departures from normal for May, 2018, showing the regional nature of the record U.S. warmth that month (graphic courtesy of WeatherBell.com).

When do you suppose the hottest temperature ever recorded in New York was? Clearly, with global warming, it must be in the last 20 or 30 years, right?

Wrong.

It was 109 deg. F. on July 22, 1926 in Troy, New York. In contrast, the state record for the coldest temperature was much more recent: -52 deg. F on Feb 18, 1979, at Old Forge, New York.

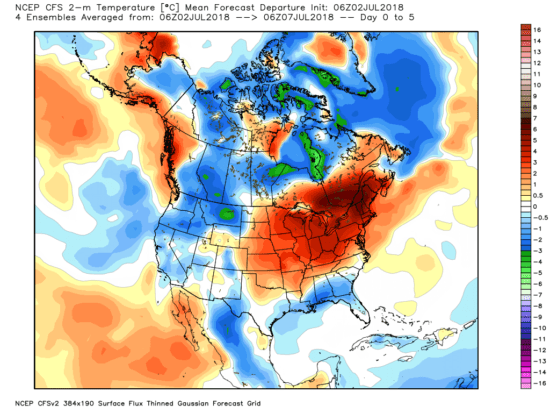

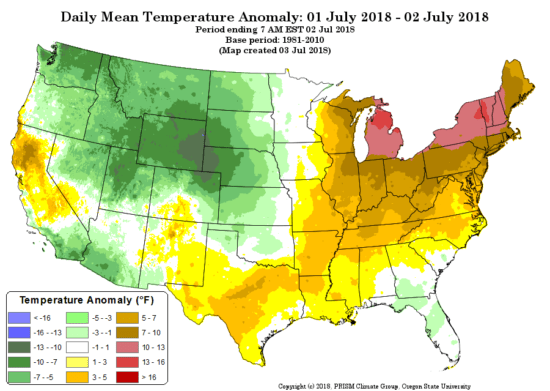

What about this week’s heat wave? Let’s look at NOAA’s GFS forecast model 5-day average temperatures for this week (Monday through Friday, July 2-6, 2018, graphic from WeatherBell.com):

Fig. 3. 5-day forecast average temperature departures from average over North America from the GFS model (graphic courtesy of WeatherBell.com).

As you can see, the excessive heat is (again) regionally isolated, which is exactly what we expect for weather… not for climate change. See those colder than average areas? Why aren’t those being blamed on climate change, too? They look like they approximately cancel out the warm area over the Northeast U.S., which is often the case for weather (not climate change) variations.

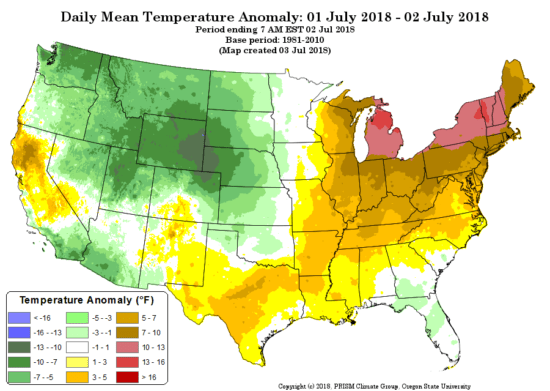

That was a 5-day forecast for this week. Next let’s look at what was actually observed over the last couple days (July 1-2), which were very hot in the Great Lakes and Northeast:

Fig. 4. Oregon State University Prism temperature analysis for July 1-2, 2018, as departures from the 1981-2010 average.

What we see is that there were unseasonably cool temperatures in the western U.S., again an indication of a temporary and localized weather pattern… not “global warming”, which would be warm everywhere.

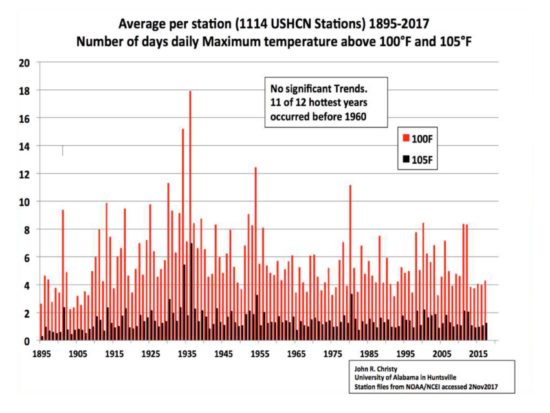

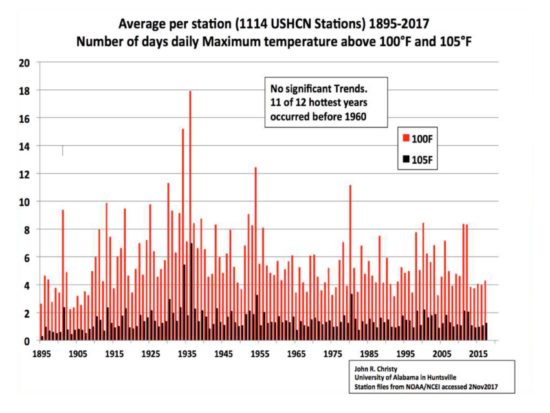

How about extreme high temperatures in the U.S in general? Here are the yearly total number of days above 100 and 105 deg. F, again for the years 1895 through 2017, based upon official NOAA data:

Fig. 5. Yearly average number of days per U.S. station having at least 100 or 105 deg. high temperatures, 1895 through 2017.

We see no trend in the number of days with excessive heat.

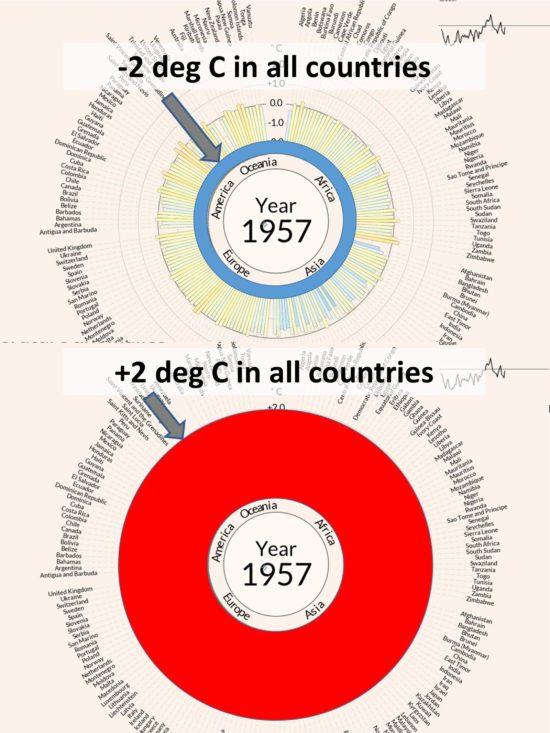

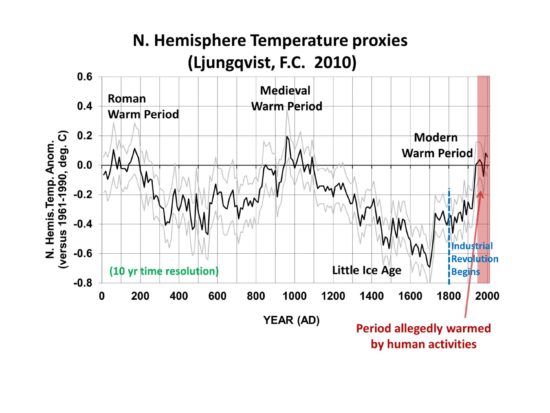

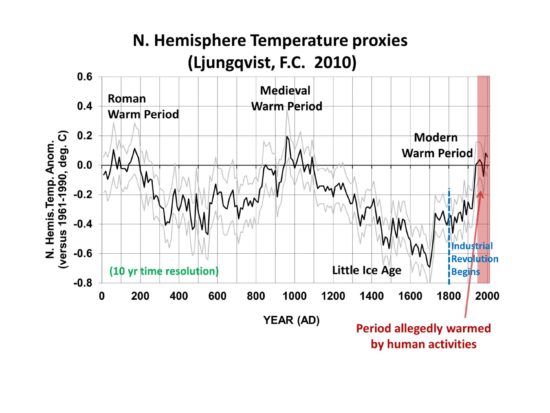

So, what do we make of the claims in the Public Citizen memo? Well, they mention that we have seen 1.1 deg. C of warming since the Industrial Revolution. Think about that. Less than 2 deg. F warming in about 200 years, part of which is likely to be natural, based upon temperature proxy estimates over the last 2,000 years for the Northern Hemisphere:

Fig. 6. 2,000 years of Northern Hemisphere temperature variations from an average of a number of temperature proxies. The period of substantial human-caused warming is generally agreed to be only since 1950 (U.N. IPCC AR5).

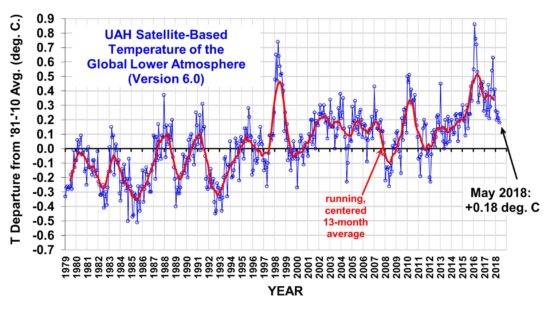

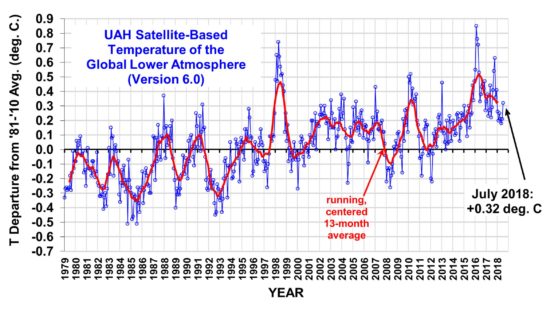

Am I claiming that there is no such thing as human-caused warming? No. I’m claiming that it is overblown. The Public Citizen memo makes much of recent record warm years clustering together, which sounds alarming — if one doesn’t mention the small fractions of a degree involved. If there was no natural year-to-year variability, and the temperature was increasing at 0.01 or 0.02 deg. F every year, then every successive year would be a record warm year…but who would care? The rate of ‘global warming’ is too weak for any one person to notice in their lifetime.

Furthermore, we already know the climate models (which are the basis for proposed changes in energy policy to get us away from fossil fuels) are producing generally twice as much warming of the atmosphere-ocean system as has been observed. The most recent energy budget analysis of surface and deep-ocean warming suggests that the climate system is only half as sensitive to our CO2 emissions as you are being told…. maybe 1.5 deg. C of eventual warming from a doubling of atmospheric CO2. At 410 ppm, We are currently half way to doubling.

And even THAT reduced estimate of future warming assumes ALL of the warming is human-caused! If a portion of recent warming is natural, the less the human-caused global warming problem becomes.

Finally, the Public Citizen memo claims that today’s technology would already allow 80% to 100% of our energy to come from renewable sources. This is patently false. Solar and wind are relatively diffuse (and thus expensive) sources of energy which are intermittent, requiring fossil fuel (or nuclear) backup. It would be exceedingly expensive to get even 50% of our energy from such sources. Maybe someday we will have such technologies, but until that day arrives, the massive amount of money that would be required to achieve such a goal would worsen poverty, which historically has been the leading cause of premature death in the world.

Home/Blog

Home/Blog