Why is it that a bible-believing scientist’s views on science are automatically discounted by some people?

I usually try to avoid the “R” issue, except that Ethan Epstein of the Weekly Standard chose to take a swipe at me in his otherwise good article on our dean of climate skeptics, Dick Lindzen.

Normally, I just ignore this stuff, but my e-mail has been blowing up in the last couple of days. So, against my better judgment, here are some thoughts on the subject…more for the benefit of those who are more outraged than I am (I expect to be attacked).

First, the hypocrisy. When warmist scientists like Sir John Houghton use the Bible to support action to fight global warming (e.g. his book Global Warming: The Complete Briefing) that was OK with everyone. Same with Katherine Hayhoe and Thomas Ackerman.

So, I guess it depends upon whether the bible-believer agrees with them before the warmists decide to trash Bible-believing ways.

In the case of global warming skeptics, I suppose the accusation is part of the assumption that bible-believers feel that “God is in control”, and so everything will turn out OK no matter what we do. Go ahead and pump all the CO2 into the atmosphere you want. The Big Guy will take care of it.

Except that I don’t put myself in this class. I readily admit that we have more than enough nuclear weapons to virtually wipe out humanity. I admit that evidence of human pollution can be found in almost every corner of the world.

In other words, we know that humans are capable of creating a huge amount of misery for ourselves, which we have done repeatedly down through history. Catastrophic global warming could, at least theoretically, be just one more example of this.

Except that I view CO2 as one of those cases where nature, on a whole, benefits from more of our “pollution”. The scientific evidence is increasingly supporting this position.

This is not a big stretch considering that CO2 is necessary for life to exist on Earth, and yet only 4 molecules out of every 10,000 in the atmosphere are CO2. Venus and Mars have atmospheres that are almost 100% CO2; life on Earth, in contrast, has sucked most of it out of the atmosphere. No matter how much we produce, nature automatically takes out 50% and uses it.

Epstein incorrectly assumes that I support the wording of all of the positions of the Cornwall Alliance, as stated in their Cornwall Declaration. But the Director of the Cornwall Alliance knows I don’t. We’ve discussed it.

Nevertheless, I still support the work of Cornwall. Seldom does a member of an organization agree with all of that organization’s stated positions.

Why do I support it? The central reason is I believe that current green energy policies are killing poor people.

Anything that reduces prosperity kills the poor. This is the single biggest reason I speak out on global warming, and why the Cornwall Alliance speaks out against policies which end up hurting the poor much more than they help.

Radical environmentalism is interested in seeing more people dead than alive. I don’t care what their press releases say. I’ve debated enough of these folks to know that their biggest complaint is that there are too many people in the world.

Some have claimed that the Earth would be just lovely without any humans. (Extra points for anyone who can spot the oxymoron there).

On a more superficial level, the accusation is often that the Bible-believing scientist “rejects settled science”, in my case the naturalistic “explanation” for the origin of life. How can anyone trust a climate scientist who rejects “settled science”?

Except this claim reveals an appalling lack of knowledge on the part of the accuser. In general, nothing in science is ever settled. And in particular, no one knows how life arose from non-living matter. It remains a mystery today.

Belief in the naturalistic origin of life is just as religious as the belief in a creator. Even well-known evolutionists have admitted this.

The scientific evidence for a “creator” is, in my opinion, stronger than the evidence that everything around us is just one gigantic cosmic accident. I have no trouble stating that — and defending it — based upon science alone. No need to quote the Bible.

But why should any of this matter for real, observable science, like climate change? Belief in macroevolution is a religion, not science. It is an organizing system of thought, a conceptual model of origins, a worldview, which the evolutionist must fit all of his observations into.

The only explanation I can think of for the Weekly Standard swipe at me is that Mr. Epstein is one of the great sea of journalists who has a considerable breadth of knowledge of many subjects, but only limited depth.

Epstein is probably not aware that science is based upon a set of assumptions — unprovable assumptions. That nature is real. That humans are capable of knowing its true nature. That nature is unified.

The existence of the universe itself violates either the 1st or 2nd Laws of Thermodynamics. That’s why cosmologists must invent physics no one has ever observed to explain how everything came to be.

Is that “science”? Really?

Epstein doesn’t understand that even atheist scientists are also guided by their religious belief that there is no creator. All scientists interpret data based upon their preconceived notions.

In Earth science, I find most researchers believe nature is fragile. But that is not a scientific position, it is a religious one. No less religious than my view that nature is resilient.

In short, there is no such thing as an unbiased scientist.

Furthermore, apart from religious considerations, not all scientific problems are created equal. Surely even journalists are capable of understanding that.

For example, the force of gravity is relatively simple, and we can predict the position of the planets far in advance with great accuracy because gravitation is just about the only force that needs to be considered in those calculations.

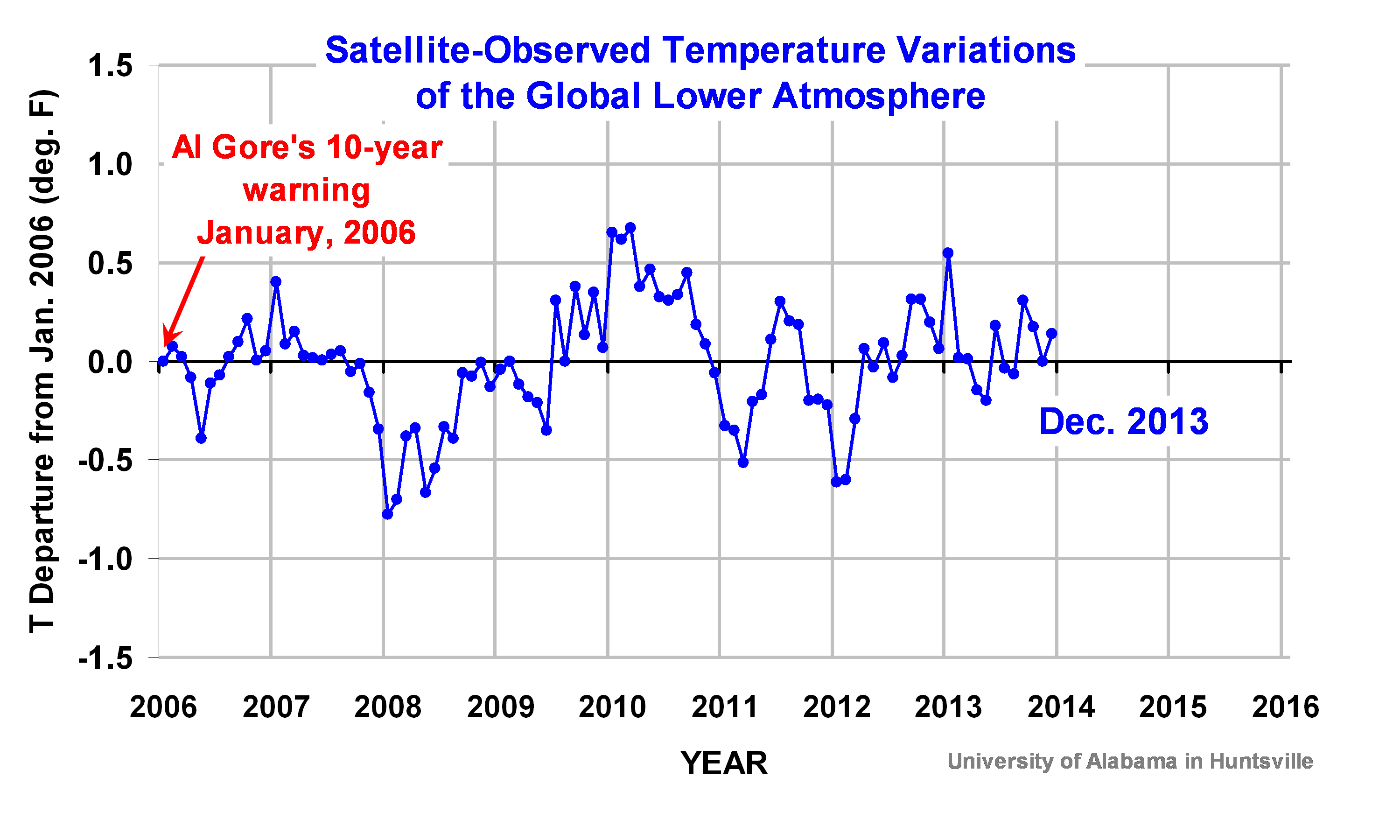

But the complexity of the climate system, and especially how it varies, is orders of magnitude more difficult to understand. It currently exceeds our ability to usefully predict its future state. Who can look at the epic failure of the climate models to explain past (let alone future) tropical temperatures over the last 30+ years, and still think that scientists can foretell climate?

And if scientists ever are able to “create life” in a test tube from non living chemicals, through all of their hard work and creativity, exactly what will that have proved?

That life could have arisen by chance? Really? Think about it.

Furthermore, life has to do more than just come into being. It has to reproduce. How does that happen by chance? Researchers have computed the probability of it happening to be essentially zero.

I’m afraid my faith isn’t strong enough to believe in such silliness.

And if you are going to comment, “Exactly what research shows all of this, Dr. Spencer?” Well, to paraphrase (and with apologies to) William F. Buckley, Jr., “Do your own damn Google search.”

Home/Blog

Home/Blog